- Home

- Ian G Moore

Playing the Martyr Page 7

Playing the Martyr Read online

Page 7

‘This is Nicolas Marquand, Messieurs. He came to offer his condolences.’

Marquand, realising his cue, put the bottle down and came striding out confidently. ‘Gentlemen, afternoon.’

‘I’m Commissaire Aubret, Monsieur Marquand, I believe you’ve already been kind enough to speak with two of my officers. This is Monsieur le Juge Lombard, who is directing the case.’ Marquand shook hands with Aubret and offered a hand to Lombard, who took it coldly.

‘Good afternoon, Monsieur. I’m sure we’ll be seeing each other soon enough.’ There was a slight edge in Lombard’s voice which wasn’t lost on Marquand, nor was the coolness in the eye of the juge. Marquand looked like he was about to say something but his mobile phone rang before he could speak. He answered it, unable to hide his relief at the interruption and made no attempt to hide the conversation.

‘It’s my wife.’ He said. ‘Yes chérie. I am at Helen’s now, just about to leave… Of course… No. I won’t forget to go to the pharmacy… Fifteen minutes… Bises.’

He turned the phone off and turned back to Madame Singleterry.

‘Helen, I must go, but again, if there’s anything I can do, we can do… please call.’

‘Of course Nicolas, and thank you.’ They kissed, a little too formally to Lombard’s mind, and Marquand addressed the two other men.

‘Gentlemen, the same goes for you. Whatever I can do to help.’

‘Thank you, Monsieur.’ It was Aubret who replied while Lombard stayed silent.

‘Shall we go inside, gentlemen? It’s a little too warm outside, I think.’ Helen put her dog down and went in through the door. Aubret followed her immediately and a moment later so did Lombard, but not until he had watched Marquand type in the private code on the inside of the Singleterry gate.

He walked down a bright corridor, past numerous floral displays, in the direction of where he assumed the sitting room must be. He turned left through an archway and into a vast open-plan room. In it were enormous sofas, a dining table for at least a dozen people and a billiard table with no pockets, in the French style. Helen Singleterry was waiting for him. He went past her to the billiard table, keeping his back to her to draw her fire.

‘That was rude and unnecessary. You seem to have made your mind up about me already, Monsieur le Juge.’ She almost spat his job title at him. ‘And it’s obvious that you disapprove of something too.’ Her hitherto excellent French was now faltering due to her emotion. She was trying her best to appear defiant and strong, with her chin held high, but Lombard could tell that she wasn’t as strong as she wanted to make out. Her hands shook, her eyes couldn’t hold his own. Perhaps he had misjudged the situation; the look on Aubret’s face suggested as much. Not that it overly bothered him, it would make a change from platitudes about grief and condolence. It was a handy ice-breaker. ‘Nicolas is a good friend, and you treat him like he was a dog on heat, sniffing about. God knows what that would make me!’

‘I’m sorry, Madame.’ He said slowly and softly and turning as he did so, and opening his arms suggesting a contrition that he didn’t feel. ‘Genuinely I am. But, whether I approve of anything or not is irrelevant. It is, however, very much my business.’ He smiled disarmingly but it did nothing to quell her anger.

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’ She shouted. ‘Is Nicolas a suspect? ‘Am I a suspect?’

‘To be fair, Madame,’ interrupted Aubret, ‘this is a murder enquiry and you are the widow of the victim. At this stage everyone is a suspect, and that includes you.’

Lombard was grateful for his colleague’s bluntness. Some situations called for it, some didn’t, and in Lombard’s possibly unfair opinion Aubret rarely knew which was which, but it worked here.

Helen sat down on a large, quite worn, Chesterfield sofa and Max, with difficulty, jumped up to join her. Lombard leant nonchalantly against the billiard table and folded his arms loosely. ‘I honestly hadn’t thought of it like that,’ she said, looking at the dog, instead of them. ‘I mean, you don’t, do you? Unless you are guilty I suppose.’

She went silent. Quietly, lovingly stroking Max as if the two men weren’t there. She was a good-looking woman, though her features were maybe too angular, too harsh, too strong for passive beauty. But together with her obvious force of personality and elegant, almost ballerina-like movements, it meant that even in her mid-forties, she was very attractive. She commanded attention. And, Lombard sensed, she was used to men feeling the need to fill in the silence around her, desperate to please. He was no different, though he hated to admit it to himself.

‘Let’s start again, Madame. The Commissaire here you know, and I am Juge Matthieu Lombard. I have been appointed to direct the investigation. Firstly, my condolences.’ Lombard, an old-fashioned man when he needed to be, almost bowed at the end of the sentence.

With a hint of amusement, her anger having quickly subsided, she nodded back. ‘Thank you,’ she said quietly, suddenly looking very tired. ‘And I’m sorry. It’s been a pretty rotten twenty-four hours.’ She put Max down on the floor and slowly wiped the dog hair from her trousers. ‘A juge, though? I watch all the crime dramas, isn’t it unusual for a juge to be out and about? Aren’t you normally sitting behind an expensive desk and making the poor policeman’s life a miserable one?’ She looked at Aubret, and addressed him directly. ‘That’s the television stereotype.’

Aubret nodded in response and got out a notebook, as if he could wish all stereotypes were true by playing up to one.

‘I like to do things differently,’ was all Lombard said, clamping down on his inner sarcasm on just how many ways there were to make the policeman’s life a ‘miserable one’. ‘Also,’ he added cautiously, ‘I am half-English and because your husband was English, it was felt I might be well-placed to help.’ He hated speaking so formally, but sometimes there was no choice.

‘It’ll save money on interpreters too.’ Helen said caustically.

‘Your French isn’t that bad.’ He fired back immediately, and she nodded in acknowledgement. ‘Now, I know you’ve made a statement already, but for my benefit I’d like to go over a few things if you don’t mind.’

‘No,’ she said wearily, though not obstructively. ‘No, of course not.’

‘You are quite a bit younger than your late husband, Madame?’ The directness of the opening question took Helen Singleterry completely by surprise. It was a style that over the years he’d perfected. She had already mentioned it herself, thanks to TV everyone these days knew what to expect from an official interview. The French television channels were full of American, British and, sometimes even French cop dramas, most of them emphatically procedural. Over recent years he’d realised that these programmes had become almost like personal memories to suspects or witnesses, like they themselves were living in a comforting fiction and they could guess what happened next. Lombard preferred to nudge them out of that comfort zone, and liked to begin with what the Americans called a curveball; what his English grandfather had called a ‘googly’.

‘That wasn’t in my statement.’ It wasn’t an angry response, just pointing it out. ‘Eighteen years younger,’ she added flatly, almost without emotion, as though it was a question she had often answered.

Lombard stayed silent, indicating that she could elaborate.

‘We met on a French exchange. I grew up in Reigate. He was a teacher with one of the English schools there, I was a pupil with another school which was on the same trip. I was sixteen.’ She said, and Lombard thought he noticed a tinge of regret.

‘Was he married at the time?’

‘Yes he was.’ It was an emphatic statement. ‘Are you going to get all upset again?’ She met Lombard’s eyes, challenging him. She clearly felt comfortable being in happy defiance of the world, trying to cause others discomfort, thought Lombard; which is a dangerous trait.

‘I’ll try to curb my prudish tendencies,’ Lombard said with a twinkle in his eye.

‘There was no…’ Helen pa

used looking for the right words. ‘Our relationship didn’t properly begin until after he ended his first marriage, if that’s what you wanted to know. We returned to England after the exchange and he divorced his wife. A year later, once I had left school… we began a relationship then. I had moved up to college. We came back to France when Graham took early retirement, five years ago.’

‘Any children?’ Aubret asked, feeling like a spectator.

‘A son from his first marriage. Also called Graham. They haven’t spoken in years.’

Lombard caught Aubret’s eye, an acknowledgement of the dim view both of them took of a father giving his son the same name. It didn’t go unnoticed by Helen.

‘I know. Personally I’ve never understood why a son is given the same name as his father either, especially Graham!’ She let out a cruel laugh. ‘We joked about it all the time. My husband hated the name Graham! It wasn’t his idea. His first wife, Janet, bless her, she was so devoted to him, obsessed almost, insisted on naming their son after him. Suffocating for all of them I imagine.’ She went silent suddenly, the humour in her face was gone, her poise disturbed. ‘She’s dead too, poor thing. Years ago. Sorry, I’m shaking all of a sudden. I’m actually quite angry. Not with you. Just… this.’

Lombard had come to the conclusion that grief was tidal, that it came sometimes just lapping in unnoticed until you were drenched in it. Or it came in great big thunderous waves which no matter how violent, you had a compulsion to dive towards. Though he knew the emotion, he didn’t quite trust Helen Singleterry’s manipulation of it.

‘And you’ve had no contact with the son?’ Lombard started to pace around the room.

‘I’m not the maternal type, I’m afraid.’

‘I meant in terms of letting him know about his father.’ He stopped by a writing desk where there were a collection of photographs only of the two of them and the dog. All fairly recent looking, within five years he’d have guessed, since they had moved to France.

‘Ah. Sorry. I see. Well I’ve sent an email – I know I should have rung but I wasn’t up to it – to a distant relative in England. I’ve not heard back yet.’ Her eyes followed Lombard’s movement closely.

‘When did you last see your husband alive, Madame?’

‘Well. It was Saturday night at the fête. Everything seemed to be OK. Everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves. All except poor Graham, of course.’

‘Why is that, do you think? Had there been a falling out?’

She sighed heavily. ‘Oh, I don’t know. Since that bore Allardyce died a few weeks back, Graham hadn’t had anyone to argue with. And I thought he was rather looking forward to Saturday. It was largely his idea, this Joan of Arc thing, together with Monsieur Galopin…’

‘That’s the Notaire,’ Aubret interrupted.

‘I don’t know why he wasn’t enjoying himself. I think maybe he was incapable of doing so. Perhaps that’s harsh, and I don’t mean it to be.’ She looked across at the photos too. ‘He wasn’t always that way.’

Lombard came and sat opposite her.

‘As he got older he didn’t seem able to relax.’ Max jumped up next to her again and she smiled at him, and hugged him close. ‘Any brief moments of happiness were always clouded by the thought that they wouldn’t last very long. Which, of course, they then didn’t.’ She leant forward to pick up a glass of water from the table in front of her. ‘When I first knew him he was different. He met me and divorced his wife on a whim and that sense of… I don’t know… of… of life, I guess. Living. It left him. Maybe you just get scared as you get older.’

‘He wasn’t an easy person?’

‘No. No, not in the last few years certainly. Not since we’ve been here really, which is sad. He took early retirement promising himself a stress-free life and “living like the French” he always said. “Time to get my priorities right.” “Live life at a slower pace.”’

‘But that didn’t happen?’

‘Does it ever?’ She asked. ‘We’ve been here long enough to know that whatever expectation people might retire here actually have, it’s still retirement. It’s still winding down. So, no. It didn’t happen. Worse, rather than let the French attitude dictate him, he tried to let his Englishness – and he was very English – he let his Englishness dictate the French. He would tell them how things were done back home, and stuff like that. He once went in to the big Bricomarché next to the supermarket, and told the manager that he should open on Sundays because that’s when people did DIY. The poor man thought he was crazy. It was funny to watch at times.’ She paused. ‘It’s not funny now.’

‘So you think he got a bit uptight at this fête and took himself away, then?’ Aubret sounded sceptical.

‘It’s possible, Monsieur le Commissaire, yes. He was aware of how difficult he could be and – for my sake – he would generally have an early night rather than cause a scene.’

‘He didn’t come home, though.’ Lombard was watching her intently.

‘No.’ She said quietly.

‘And you didn’t raise the alarm?’

‘I didn’t know. He often slept in his “den”. The sous-sol. I just assumed he was there, pottering about.’

‘He didn’t argue with anyone on Saturday night, then?’

‘He wasn’t one for confrontation, apart from Allardyce who loved to needle him, and he wouldn’t see it as confrontation anyway. He would say his opinion – the food was too late, the lights were in the wrong place, Joan’s standard was upside down – and if you disagreed, you were simply wrong. The last I saw of him he was pointing out to Émile, that’s Émile Lagasse, he owns the Lion d’Or, something about the wine. I don’t know what, I couldn’t hear him, but Émile looked mortified as he always does.’

There was a brief silence again, broken after a few moments by Lombard, ‘Are you having an affair with Monsieur Marquand?’

She looked him directly in the eye. ‘No,’ she said emphatically rather than with the defiance of earlier.

‘I have to say that it looked that way when we arrived.’

‘Then that’s your problem really, isn’t it?’ She stood up and walked towards the mantelpiece. ‘And says more about you than it does me. I don’t know what you were expecting? The bed-ridden grieving widow presumably? A human wreck in a puddle of tears? Well I’m sorry to disappoint you! I’m not quite sure what the form is, I’ve managed to avoid the need for grief for most of my life and I didn’t know there were rules. I’m devastated Graham’s gone, not sure I even quite believe it yet, but if you think I’m going to fall down and allow you some patronising role with a weak woman, you’re wrong.’ Aubret looked like he was about to apologetically interrupt, but she cut him off. ‘Nicolas is a friend, a good one, but the truth is this: we are not having an affair. Though my own late husband, who I loved dearly, even suggested that we should! Can you believe that? His own suggestion! He became, oh, disinterested, in anything physical and was sensitive to my own frustrations… maybe it was an age thing, I don’t know. Christ, listen to me, I sound like a bad magazine article. He thought that it would make me happy. He liked Nicolas, he thought “it would be a good fit”. He was a very practical man, my husband. He liked “good fits” and convenience.’

‘You are close, though?’ Lombard prodded and something in the way he said the word ‘close’ meant that it was laden with meaning.

‘You are judging me again!’ Anger flashed in her eyes, albeit briefly, ‘I suppose it’s your bloody job, but I didn’t have to tell you that! I make no apology for what I say or for what you think, especially as my own husband would not have demanded one. We are close. We are no more than that.’

There was a long pause.

‘Madame, who would want to kill your husband?’

She looked up at Lombard, who could see tears beginning to form. Were they real ones? He couldn’t tell, why was he even in doubt?

‘How the hell do I know?’ She shouted. ‘My husband…’ she continued m

ore calmly, though it took obvious control. ‘I’ve heard him described as being like a mole, a harmless, needy-looking creature but one that then arrives uninvited and churns up a perfectly decent lawn. A horrible thing to say. He always said that he was “just helping” people, but some people don’t like being helped and I told him that often. I doubt there’s a business in town or a new arrival, English or French, that he hasn’t “advised’” or tried to help at some point. He was like that. He became like that.’

A few moments later she showed them to the gate, her small dog once again in her arms, its growling resumed.

‘Please don’t misunderstand, about Nicolas and I. We are just friends, and I wouldn’t want him to get into any trouble for what I’ve told you.’ She was talking as the gate started to close behind Lombard and Aubret. ‘His marriage is not an easy one and nor was mine at times…’ She stopped. ‘I’m scared, gentlemen. Scared of what happens next to me, here, now, scared that nothing will happen maybe. Our age difference always meant that I’d probably reach a stage of life alone anyway, not this early maybe, but I’ve had years to think about it and prepare for it. And now I find I’m not prepared. I’m not prepared at all.’

***

Lombard and Aubret drove back into Saint-Genèse, down the hill and over the bridge.

‘She held herself together pretty well for most of that.’ Aubret was chewing on the ubiquitous Gaviscon and was more interested in provoking the brooding Lombard than providing any earth-shattering conclusion.

‘With a little help from her friends,’ came the moody reply.

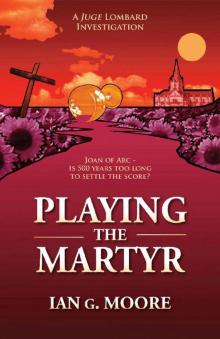

Playing the Martyr

Playing the Martyr