- Home

- Ian G Moore

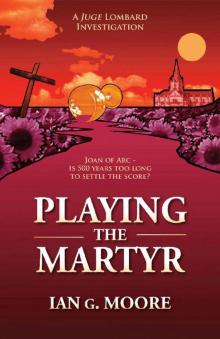

Playing the Martyr

Playing the Martyr Read online

Chapter 1

He knew he was dying. He just hoped it would be over soon, that he might finally earn his peace. The pain was bad enough, but the dull, endless rhythm of it, repetitive and judgemental like church bells, was worse. Beating him further down, like a mallet on a tent peg. At first, he’d tried catching the pain off guard, hoping that sudden movements would take the searing paroxysms by surprise, and that survival was a possibility. But he was weaker now, the pain didn’t have to work as hard and he willed it on to finish the job.

Fighting against the physical spite, he managed to open his eyes. Without focussing fully he could tell it was business as usual in the valley. But what was normally so comforting now felt mocking and uncaring. The sun, already warm, was to his left and the shimmering river Loire, at the end of the sloping field looked calm as it always did. Its benign inviting surface hiding a dangerous, lethal undercurrent. The birds were busy too. Competing with the noises in his head they were cheery, gossipy, full of late-spring chatter, but showing a cruel disregard for the man on the cross.

His body, numb in parts, feverish with agony in others, didn’t feel like his own anymore; as though he was already trying to leave it, or disown it completely. His mouth and throat bubbled with blisters; his lips were parched and cracked. His hands, though they felt so, so far away, burned too. The skin on them tight, as though they’d been outgrown. He wore a heavy winter coat, whose he didn’t know, but with the already simmering heat of the morning, it was boiling his insides like a bag of rice. The only respite it offered was the shadow from the hood, shielding his eyes from the piercing sunlight.

Another dull thump roused him, but this was different from the one in his head. This was elsewhere, and he painfully tried to focus his eyes on the near distance. Despite his watery vision, he could make out a car at the bottom of the hill, and someone, no more than a blurred outline, moving his way. His heart started pounding suddenly, shaken from its stupor as hope re-energised it.

‘We’ll use my phone, Jane…’ the approaching figure shouted up the hill, and it was then he sensed another presence standing nearer.

‘I don’t know Lucy. Maybe it’s best just to...’ The voice was right beside him.

‘Rubbish! Come on! Put your arm around the scarecrow’s shoulder. We’ll send the picture to that two-timing dick. Show him you’ve upgraded!’

In his head he screamed. His heart beat faster and faster, louder and louder too. How could they not hear that? How could they not hear the deafening sound of the torture inches away from them? He had an image of himself thrashing about on his wooden cross, but was he even moving? The burning pain, like violent electric shocks, was permanent and all-consuming, physical white noise at a thousand decibels. But the despair, the sheer violence of his frustration was now worse than the physical suffering.

‘Put that necklace he got you on it.’ Again, the sharp stab of hope jolted him. ‘Go on, lift the hood up so we can see its face a bit more.’

‘I don’t really want to touch it.’

‘Oh, get on with it! It won’t bite!’

She was so close now that she cast a shadow over the lower half of his face. He felt her gently lift the hood. Then he saw her, her arm was outstretched towards him, but her head was looking the other way. Look at me! Please, look at me! But his desperate plea just echoed around his head. Without looking round, she let go of the hood, letting it fall back over his imploring eyes. Back into the shadow.

‘No.’ He heard her say, ‘I don’t want to touch it.’

‘Oh for Heaven’s sakes. It’s not real! Hang the necklace off its arm then.’

Jane did as she was told, without touching his arm.

‘That’s it! Got it.’

‘Let’s have a look! Let me see.’

‘Sent it! That’ll show him!’

‘No, Lucy! You’ve sent it to him?’ The voices, like his own spirit, were fading now, moving away and leaving him.

‘You have his number? I didn’t know you had his number.’

Real church bells started ringing in the distance, calling the faithful to worship. A tuneless, metallic demand that slipped into the same sluggish rhythm as the pain behind his eyes. He knew then that it wouldn’t be long, each bell toll was just marking out time like a large metronome, each heavy thump more painful than the last. Duh-dum, duh-dum, duh-dum, duh...

Suddenly his hood was ripped back and the sunlight blinded and burnt him some more. And then the final stolid reverberation of the church bell, in step with the leaden booming in his head, also timed perfectly with the final blow that came crashing ferociously through his skull. Briefly the birds scattered and, for a few seconds, were even silent. Then they returned, resuming their babble as they did so, nothing to see here, they were saying, nothing to see here. The scarecrow had failed again.

Chapter 2

Matthieu Lombard ambled along the rue Nationale in Tours enjoying the warm evening sun. There was the hint of a light, baffled smile on his face, thus exercising muscles he hadn’t used in a while; the smile at odds with his cool blue, slightly down-turned eyes. He wasn’t a tall man, but good posture made him look so. He also looked like a man who’d had a great weight lifted off his shoulders but one who didn’t really know how to deal with it. It was an air of bemused contentment. And if that was still some way short of actual contentment, then it suited his cautious nature and was still a better mood than he’d had for some time.

He was already running late, and late late too, not the usual Tourangeaux fifteen minutes late. But when you’ve just made a life-changing decision maybe it’s best to enjoy the moment rather than rush to make it happen. Or, in this instance, rush to keep a promise you weren’t that keen on keeping in the first place. His lateness was unavoidable anyway. Yes, he’d promised to be at the bar for half seven, but when the call came through from the Commissariat de Police at half six, he’d had no choice but to prioritise that.

‘Lombard?’ He’d recognised the weary voice of Sergent Brosse immediately, a long-time colleague, but one whose patience was now obviously running thin. His heart had sunk immediately, knowing exactly what and, more to the point, who the call would be about. ‘We’ve got her here again, Monsieur le juge. Please come and get your mother now. Or,’ there was an apologetic sigh, ‘or this time we charge her.’

He’d never liked going to the Commissariat. A squat, ugly concrete building on the rue Marceau completely at odds with the grand architecture of much of the centre of the old city. It stood out like a municipal van at a classic car rally. The plan was simple: get in quick, get his mother out with as little fuss as possible and hope that he didn’t bump into anyone of authority that he knew. Those meetings, though mercifully rare, were difficult enough without his volatile mother making things even more awkward.

He strode in purposefully through the double doors, knowing the best way to hide yourself in bureaucratic buildings is to look like you belong there. Certainty is the camouflage used by all civil servants. He approached the desk and Brosse, who had been impatiently waiting for him, waved him around the side. The electronic security gates slapped open sharply, emitting an angry hiss in the process, as though they were equally fed up with this regular carry-on.

Brosse, heavy-set in the mould of police sergeants worldwide, wore a crumpled shirt that showed visibly how he wasn’t coping with the unseasonal heat. He was waiting impatiently for him on the other side, and they shook hands without warmth.

‘You know, Monsieur le juge, we’re busy enough this evening without having to deal with your family problems.’ He turned slowly, like a cruise ship in a small port, his need to get this business over and done with quickly battling his desire to stretch out the moment. Family problems.

The insinuation was clear, this was Lombard’s responsibility and in the opinion of Brosse, he wasn’t despatching it with a great deal of success. ‘This is the fourth time since Easter you know, we can’t keep turning a blind eye.’ An equally clear message: your influence, the sergeant was saying, such as it ever was, is fading around here and you’ll soon be treated like every other civilian.

‘I’m very grateful to you, Sergent.’ Lombard sighed, sticking to the practised script. ‘What was it this time?’

‘She was protesting in the food hall at Monoprix. Nutella specifically.’

‘Nutella? The chocolate spread?’ This seemed more specific than the usual ‘Mother Earth’ problems, as he called them. If she was going to start targeting individual products, there really would be no end to it.

‘Yes, Nutella.’ Brosse snapped back. ‘My grandkids won’t let us have it in the house either. Something about palm oil and orang-utans. I don’t get it myself. I mean, fair play to her, you know, in one way that is…’ He paused to regather his anger, ‘But you can’t go shouting ‘murderers’ at people in Monoprix on a Sunday lunchtime.’ He stopped and turned to Lombard, a look of confusion on his face while he tried to find the right words. He decided to keep it simple instead. ‘Seriously. This has to stop.’

Lombard shrugged unhelpfully. What exactly was he expected to do? His mother, Charlotte Lombard, was now nearly 70 and most certainly wasn’t ‘ill’ in any way. He knew people who had wiped their hands of their parents’ behaviour and blamed age, Alzheimer’s disease, or something else; anything to abdicate responsibility. But his mother’s behaviour wasn’t the result of fading faculties or age. She was a passionate woman, that’s all, so they said. Angry would be nearer the mark though, and permanently so, and living in a world that now offered multiple opportunities to the easily affronted. If you had a cause, she’d more than likely join it. Climate, animals, feminism, peace, anything going and she’d back it with the fervour of a jihadist and with an enthusiasm and dedication she certainly hadn’t given to parenting.

She was sitting by a desk in the corner and looked tired and small. She was still holding on to her protest placard too, which hung upside down at her side, ‘You Eat Orang-utans for Breakfast!’ it read. As subtle as ever.

‘Maman?’ Lombard got down on his haunches and looked up into his mother’s angry face.

‘Well it’s about time!’ Her grey-green eyes burned fiercely, and in a way her anger made her look younger and more like the beauty she had once been. Still an elegant woman, she made no effort to dress that way anymore, preferring the ‘uniform of the oppressed’ as she called it, drab, hard wearing clothing, though her hair was immaculate and the make-up on her wrinkled face perfectly applied. ‘Look what they’ve done to me!’ She tried to lift her left arm but it was handcuffed to the desk. ‘I’ll sue! Sue for police brutality! You’re a magistrate, I want to bring a civil action!’

He looked at Brosse, who rolled his eyes. ‘Was there a need to restrain her, Sergent?’ Lombard affected a formal air, though making it clear too that he wasn’t taking the matter seriously, it was just a way to get her out quickly.

‘It wasn’t my idea.’ Brosse wasn’t playing the game and he added testily, ‘It was his.’ He pointed at an officer seated at another desk across the open plan office and who was holding a cold bottle of water to his cheek as a makeshift compress. He lowered the bottle and revealed a swollen eye and a fed up look on his face.

‘Oh maman.’ Lombard shook his head. His mother raised her chin in defiance and looked away.

‘He asked for it. The man-handling bastard!’ The policeman made as if to protest but Lombard’s mother wasn’t finished. ‘He enjoyed it too! He clearly doesn’t get any at home!’

Brosse lowered his voice and leant in, ‘To repeat. This can’t go on. I’m doing this as a favour, but this is the last time. It may even be out of my hands next time, it may have to go higher...’

‘All the way to a Juge d’instruction, you mean?’ Lombard stood and put his hand on his mother’s shoulder, which she shook off petulantly.

‘Maybe.’ Brosse paused as if choosing his words carefully, not his strong point, ‘but one that’s still working.’

Lombard turned his cool eyes directly on the policeman, who avoided their penetrating stare by bending down, with some difficulty, to unlock the handcuffs. ‘Point taken, Sergent Brosse,’ he said stiffly. ‘How’s your lad by way? Still clean, I hope.’

Thirty minutes later he stopped by the cash machine to withdraw some money. He was now short of funds having given 40 euros – way, way over the odds, at least double – to the taxi driver to take his mother home and make sure she was through the door too. He knew he should have gone himself but he’d come to a decision and didn’t want to lose that train of thought by continuing the row they’d had at the taxi rank.

‘You did nothing in there to stick up for me!’ She’d hissed at him, for once choosing discretion over the full venting of her considerable emotion.

‘You assaulted a police officer maman, caused an obstruction on private property, and accused innocent shoppers of murder...’

‘Innocent? Hardly...’

‘The fact that you weren’t charged is down to me.’

Again, it was the usual role play. From a distance, they looked like any other mother and son, the younger man holding the arm of his frail relative while they talked quietly together. Only he was holding her arm tightly so she didn’t storm off and they were both reigning themselves in, partly to avoid a family scene and partly so that a taxi might be persuaded to stop rather than drive on wanting to avoid the hassle of a domestic row.

‘Any proper Frenchman would never allow his mother to be treated like this!’ She said more loudly as she got into the back of the white Peugeot estate. Lombard, outwardly ignoring this frequent dig this regular arrow knowing it was designed to make him angry, which it did, showed the suspicious taxi driver his ID and gave strict instructions as to what he wanted for his money. She started to wriggle out again and he pushed her gently, but firmly, back in and put her seat belt on as she slumped back admitting defeat.

‘I’ll ring you tomorrow maman.’ he said loudly enough to try and assuage the doubts of the driver, and kissing her on the cheek. ‘Try and get a good night’s sleep.’

‘Just like your father.’ She said quietly, kissing him back. ‘You’re so English.’

He collected his money and receipt from the cash machine and continued his languid stroll. Brosse had made his mind up for him. He was going away. He had been drifting now for a year. Like an animal on a night-time country road he’d seen the lights approaching, knew that he had to make a leap but just didn’t know which way meant safety. But the lights were getting closer now and standing still would be fatal. There seemed little left for him here anyway. He’d had a year of compassionate leave, or unofficial suspension, call it what you will, it depended on who you asked. Either way, the Magistrature didn’t trust him to handle any cases these days, not even the petty civil ones, and certainly not more complex crimes. He was an investigating magistrate without an investigation and with dwindling authority; it was time to move on. Time to sell Madeleine’s business, sell their home and leave Tours for good. He’d always fancied running a bar somewhere anyway. Or travelling. No, a bar. By the sea. Yet somewhere remote too, away from the numbers. Of course, his mother would have to come, but leaving Tours might do her good; it might do them both good for that matter.

A new start away from the small city with the big history, loosen their ties as it were and live a simpler life outside the goldfish bowl modishness of Tours. He’d loved the place, he still did, it had been home, more or less, since he was twelve, but it felt like a children’s playground at times. You had to scramble to the top of the climbing frames to be anyone and power was shown by ascending ostentatiously the wrong way up the slide. Subtlety was old-fashioned, and he didn’t have the energy anymore, or the ambition. Not that

he’d ever had ambition anyway, something that had always played against him. He enjoyed, had enjoyed, his job for what it was and wanted no more than that. Too many used the judiciary as a stepping stone to ‘greater’ things, but that had never interested him. ‘There’s no-one less corruptible than a juge d’instruction without ambition,’ another magistrate had said to him once. ‘No-one less trusted either,’ he’d added, summing up neatly the contradiction of power and politics: who wielded it, why, over whom and, too often, for how much.

He paused as he turned into rue Colbert and took in the view. From where he stood he could see the full length of the ancient street. The medieval buildings leant in from each side as though they were shielding the strolling, oblivious Lilliputian mortals from modernity and the outside world. Every world cuisine was on this street, the outside menu boards attracting the hungry window-shoppers while a few shoeless conjurers, in search of a few centimes and a meal, performed tricks to largely disinterested passers-by. And there at the end, watching over the scene like the omniscience it purported to represent was the enormous, imposing behemoth of the Cathédrale Saint Gatien. He breathed it all in. No. Despite the city’s beauty, it really was time for a change.

A huge masculine cheer went up signalling to Lombard that he had arrived at Hurley’s Irish Pub. On one of the smoked windows was a simple sign, printed on garish A4:

QUIZ NIGHT

SOIRÉE QUIZ

THE BRITS vs THE FRENCH

(LES ROSBIFS contre LES FROGS)

Dimanche, 25 Mai

The double doors burst open spilling the noise out onto the quiet street, quickly followed by two men dressed as English knights. Their white Crusader tabards, once gleaming presumably, now stained with drink. They stumbled out of the bar laughing and hungrily scrabbling at their cigarette packets. Immediately another man followed wearing the uniform of the French peasant stereotype, as seen by the English. A striped, Breton shirt with a red neckerchief, a black beret, a painted-on thin moustache and a string of fake onions. He too was in a hurry to light his cigarette but was also laughing too hard to manage the task.

Playing the Martyr

Playing the Martyr